Natural History

The Northern spiny-tailed gecko is a nocturnal lizard native to the arid and semi-arid regions of northern Australia, particularly thriving in sandstone escarpments, rocky outcrops, and spinifex-covered terrain. Its life cycle begins with a remarkably self-sufficient hatchling stage. After a successful mating season, which typically aligns with the warm, wet seasons to optimize resource availability, the female lays a clutch of one to two eggs. These eggs are deposited in moist crevices or under rocks, where the stable microclimate helps sustain proper development. Incubation lasts roughly 60 to 90 days, depending on environmental temperatures. There is no parental care post-laying—the embryos are left to develop independently until hatching. Hatchlings emerge fully formed and are immediately capable of fending for themselves. Growth is relatively slow, with individuals reaching sexual maturity in about 18 to 24 months. In captivity, Northern spiny-tailed geckos can live up to 12 years with proper husbandry; wild lifespans are typically shorter due to predation and environmental stresses.

Behaviorally, this gecko displays highly adapted nocturnal habits, emerging from its refuge well after dusk to begin foraging and territorial patrols. Northern spiny-tailed geckos are solitary and strongly territorial, often returning to the same shelter sites night after night. They rely on scent marking and visual displays—such as body inflation, tail curling, and mouth gaping—to ward off intruding conspecifics during territorial disputes. Their hunting strategy is one of ambush predation: they wait motionless near the edges of rocky outcrops or beneath low vegetation until an unsuspecting insect or arachnid ventures too close. Their diet in the wild consists primarily of beetles, crickets, spiders, and other small arthropods. Despite their somewhat cryptic appearance and reclusive nature, they can also be quick to flee when startled, retreating into tight rock crevices where their spiny, reinforced tails block entry and deter predators. This tail is not only a defense mechanism but also plays a role in fat storage, helping them endure periods of food scarcity.

In the broader ecosystem, the Northern spiny-tailed gecko plays an important mid-tier role in the food web. As a predator, it helps regulate invertebrate populations, contributing to natural pest control within its native habitat. This is particularly significant in arid and rocky ecosystems where insect populations can fluctuate rapidly. In turn, the gecko itself is prey for larger nocturnal hunters, such as snakes, owls, and carnivorous marsupials. Its cryptic camouflage, primarily composed of mottled earth tones, helps it avoid detection during daylight hours when it shelters among rocks and under vegetation. Additionally, this species has evolved physiological adaptations such as water-conserving skin and the ability to maintain metabolic functions in high-temperature environments—traits that allow it to thrive in regions where extreme daytime heat and low rainfall are common. These environmental adaptations not only help support survival in some of Australia's most challenging conditions but also highlight the gecko's niche as a resilient and ecologically significant reptile.

Understanding the biology, behavior, and ecological importance of the Northern spiny-tailed gecko is essential for anyone interested in its captive care. Captive environments should mimic natural behaviors and conditions as closely as possible in order to support this species' physical health and mental well-being. By appreciating how this gecko interacts with its world—from the rocky terrain it calls home to the food web it helps sustain—keepers can approach its care with both scientific insight and ethical responsibility.

Conservation Status

The Northern spiny-tailed gecko is currently listed as “Least Concern” on the IUCN Red List. This classification indicates that, at present, the species maintains stable population numbers throughout its known geographic range and is not currently at significant risk of extinction. It occupies a relatively broad distribution across northern regions of Australia, primarily in arid and semi-arid habitats, including rocky outcrops, escarpments, and dry woodlands. The Least Concern status reflects both a relatively wide distribution and the absence of immediate, large-scale threats that would significantly impact the core populations. However, localized declines or fragmentation in certain areas are still possible and warrant ongoing ecological monitoring.

Despite its current stable status, the Northern spiny-tailed gecko does face threats that could impact its population if left unmanaged. Habitat degradation is among the primary concerns—intensive land clearing for agriculture and mining operations alters or destroys the rocky habitats this species relies on for shelter and thermoregulation. Additionally, changes to fire regimes, particularly increases in the frequency and intensity of wildfires, can negatively impact habitat structure and prey availability. Although the species displays some adaptability to habitat disturbance, repeated environmental changes can stress local populations over time.

Another emerging concern is the spread of invasive species, particularly feral cats, which pose a considerable predatory threat to small reptiles across Australia. While the gecko’s nocturnal and secretive behavior provides some measure of protection, predation by invasive mammals can still contribute to population decline, especially in fragmented habitats. Additionally, the introduction of invasive grass species has altered fire patterns in some areas, leading to hotter and more destructive fires that further degrade suitable microhabitats. The illegal collection of reptiles for the international pet trade has not significantly impacted this species so far, but any rise in demand could place additional pressure on wild populations.

Conservation efforts for the Northern spiny-tailed gecko focus primarily on habitat preservation and management within its natural range. Portions of its habitat are protected within national parks and conservation reserves, where land-use impacts are more strictly controlled. These protected areas play a critical role in maintaining viable populations and ecological integrity. Fire management practices, such as planned burns and firebreaks, are being used to reduce the frequency of high-intensity wildfires, which helps preserve essential microhabitat features such as crevices and vegetation cover.

While there is currently no formal recovery plan specific to this species, it may benefit indirectly from broader conservation initiatives targeting arid-zone reptiles and ecosystems. Captive breeding efforts, though not a significant component of the species’ conservation at this time due to its Least Concern status, have occurred within zoological institutions and by experienced private keepers. These programs contribute to husbandry knowledge and could play a supportive role if future declines in the wild were to necessitate reintroduction or genetic management efforts.

In summary, although the Northern spiny-tailed gecko is not presently considered at risk of extinction, continued habitat protection, fire management, and control of invasive predators are essential to ensuring its long-term survival. Reptile keepers and conservationists alike play a role in safeguarding this unique species through responsible care practices and support of conservation initiatives aimed at preserving Australia’s diverse reptilian fauna.

Native Range

The Northern spiny-tailed gecko is endemic to the tropical regions of northern Australia, with its native distribution primarily spanning the Top End of the Northern Territory and parts of adjacent Western Australia and northwestern Queensland. Its range encompasses areas near the Arnhem Land plateau, Kakadu National Park, and regions around Katherine and Darwin. This species has a relatively restricted geographic distribution compared to many other geckos, largely confined to areas characterized by rugged sandstone escarpments and woodlands within this tropical monsoonal zone.

Within its natural habitat, the Northern spiny-tailed gecko occupies a range of macrohabitats, including open Eucalypt woodland, dry tropical forest, and savanna ecosystems. These ecosystems are typically dotted with sandstone outcrops and boulder fields, which are essential elements of this species’ survival. In terms of microhabitat preferences, this gecko is highly specialized; it seeks shelter within narrow crevices, rock fissures, and beneath exfoliating slabs of sandstone. These microhabitats provide critical refuge from predators, harsh climatic conditions, and desiccation, and they also serve as vantage points for ambushing prey after dark.

The region inhabited by this species experiences a tropical monsoon climate, with distinct wet and dry seasons influencing the gecko’s activity patterns. During the wet season, which lasts from November through April, average daytime temperatures range from 85 to 95°F, and relative humidity often exceeds 80%. Torrential rains and high humidity during this period increase insect abundance, providing ample feeding opportunities. The dry season, from May through October, is markedly cooler and drier, with temperatures typically ranging from 70 to 85°F during the day and dropping below 60°F at night. Nighttime activity diminishes during the coolest and driest months, and geckos retreat deeper into rock crevices to conserve moisture and body heat.

The Northern spiny-tailed gecko is most commonly found at low to mid-elevations, ranging from sea level up to approximately 1,500 feet above sea level. Within this elevation range, the presence of rugged sandstone topography is a crucial determinant of suitable habitat, particularly in areas where rock shelters can maintain stable microclimates with moderate moisture retention. These environments buffer extreme temperatures and humidity fluctuations, a vital factor for small ectotherms.

Key environmental features essential to the survival of this species include the availability of sandstone or similar rocky substrates that provide tight crevices and overhangs, the presence of sparse ground vegetation that supports insect prey species, and relatively stable ambient humidity within shelters even during the dry season. Unlike some desert geckos that rely on burrows or loose sand for protection, the Northern spiny-tailed gecko’s reliance on rocky outcrops limits its distribution to geologically suitable areas. Consistent access to shaded, sheltered surfaces and the thermal gradient provided by sun-exposed rocks are also fundamental to this gecko’s behavioral thermoregulation strategy.

The combination of a restricted geographic range, dependence on specific geological formations, and sensitivity to climatic variability makes the Northern spiny-tailed gecko particularly vulnerable to habitat disturbance. Storm-induced erosion, human development, and wildfire can negatively impact the delicate balance of microhabitats upon which this species relies. Understanding these environmental parameters is essential for replicating suitable living conditions in captivity and for supporting conservation efforts.

Behavior

The Northern spiny-tailed gecko is a nocturnal species, exhibiting its peak activity during the nighttime hours. In its native arid and semi-arid habitats, it emerges from rock crevices or under loose bark shortly after sunset to forage and patrol its territory. Unlike crepuscular species that are active during twilight, this gecko is rarely observed during daylight unless severely disturbed or during exceptionally overcast conditions. Activity levels are tightly linked to seasonal changes. During the dry season, when temperatures can rise sharply during the day and fall sharply at night, its activity is more restricted and opportunistic. During the cooler months, particularly in regions where temperatures dip below 60°F consistently, individuals may enter a state of brumation—a period of torpor where metabolic activity is significantly reduced. This dormant phase typically occurs in concealed shelters and may last several weeks depending on local climate variations.

Socially, the Northern spiny-tailed gecko is highly territorial and solitary outside of the breeding season. Males establish and defend small territories using visual and tactile cues, often engaging in threat displays rather than direct combat. These displays may include tail vibrations, body inflation, and lateral body flattening to appear larger. Females are generally less aggressive but will defend prime oviposition sites that offer high humidity and stable temperatures. During the breeding season, which is triggered by increased rainfall and ambient humidity shifts, males intensify territorial patrols and courtship behaviors. Courtship involves a sequence of tactile stimulations including gentle nuzzling and tail undulations. After copulation, females lay a clutch of usually two leathery eggs in concealed, thermally stable microhabitats. There is no parental care post-oviposition; hatchlings are independent from birth and receive no assistance from adults.

Environmental responsiveness is a key survival trait in this species. The Northern spiny-tailed gecko uses its keen vision, which is adapted for low-light conditions, and chemosensory cues via the Jacobson’s organ to detect prey and other geckos. It is highly sensitive to temperature gradients. Upon sensing nighttime surface temperatures dropping below 70°F, individuals will delay emergence or limit locomotion to preserve energy. High humidity, especially following rainfall, often triggers increased surface activity as it correlates with heightened insect prey availability. In captivity, geckos respond well to controlled photoperiod cycles that simulate natural dusk and nighttime transitions. However, abrupt lighting changes or inconsistent temperature gradients can cause stress, marked by reduced feeding and increased hiding behavior. When approached by humans or potential predators, these geckos often employ cryptic behavior, using their irregular dorsal patterning and stillness to avoid detection. If cornered, they may engage in tail-raising displays, tail waving, or autotomy—the voluntary shedding of the tail—as a last resort defense.

One distinctive behavioral trait unique to this species is its use of a heavily spinose tail not only for defense but also for social signaling and moisture storage. The tail’s spiny texture may deter predation as it makes it less palatable and difficult to swallow. In addition, this gecko is known for its vertical climbing ability despite lacking full toe pads seen in other gecko species. It uses micro-claw engagement and body bracing to navigate rock walls and tree bark, a behavior observed extensively in the wild. Thermoregulation is accomplished through behavioral shifts such as selecting retreat sites with specific thermal characteristics rather than relying on basking. Unlike diurnal lizards that sun themselves, this gecko chooses refuge temperatures between 75°F and 85°F to passively maintain metabolic stability.

Behavioral differences between wild and captive individuals are notable. In captivity, where predators and environmental variability are absent, the geckos may exhibit more regular feeding patterns and reduced stress-related behaviors. However, territorial aggression may increase in confined enclosures if multiple individuals are housed together inappropriately. Captive geckos show less reliance on bluff threats and more frequent use of hiding when exposed to handling or overexposure to light. Enrichment, such as variable climbing surfaces, adjustable humidity zones, and feeding that encourages ambush strategies, is critical in replicating natural behaviors and reducing stress. Without appropriate environmental stimulation, some individuals may develop repetitive behaviors or show delayed feeding responses.

Overall, the Northern spiny-tailed gecko displays a combination of specialized behaviors tailored to low-light arid environments, with a significant reliance on environmental feedback for survival. Its isolated and territorial nature, nocturnal foraging strategies, and unique defensive adaptations contribute to its distinct ethological profile among Australian gecko species.

Captivity Requirements

Enclosure Design

The Northern spiny-tailed gecko is an Australian arid-adapted species that requires an enclosure replicating its natural semi-desert to open woodland environment. Juveniles can be temporarily housed in enclosures no smaller than 12 inches long by 12 inches wide by 18 inches tall. However, to support proper growth and activity, they should be upgraded to adult housing by nine to twelve months of age. Adult Northern spiny-tailed geckos require a more spacious setup, with the minimum enclosure size being 18 inches long by 18 inches wide by 24 inches tall. Larger enclosures are recommended when possible to encourage natural behavior and increased activity.

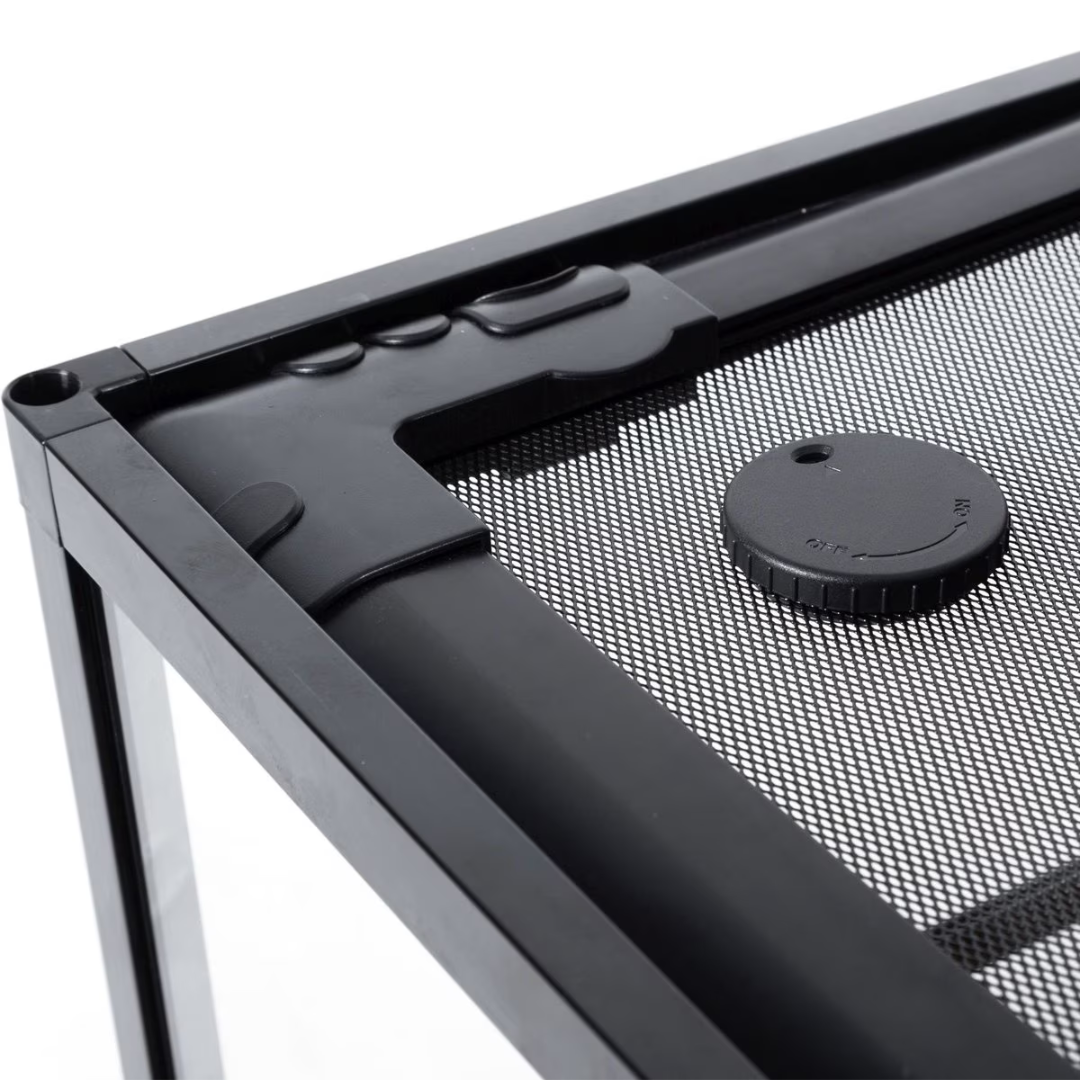

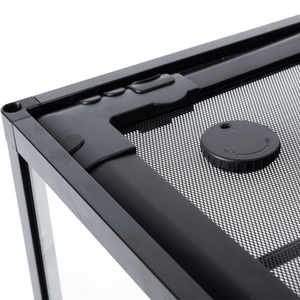

Glass terrariums with front-opening access are ideal for visibility and ease of maintenance. Enclosures should feature a screen top or vent panels to promote air circulation, but should retain enough structural integrity to hold consistent temperatures. PVC enclosures are highly recommended due to their superior heat retention, resistance to humidity changes, and ease of cleaning. Mesh-topped enclosures must be used with caution in drier climates to avoid excessive dehydration.

Geckos of this species are agile climbers, frequently found among rock outcrops and arboreal perches in the wild. Therefore, enclosure layout must incorporate vertical space with carefully placed rocks, ledges, cork bark sections, and dry hardwood branches. Multiple hide boxes at varying height levels should be included — at least one on the cooler end and one near the basking zone — to emulate rock crevices and offer secure retreat spaces. Security measures such as tight-fitting sliding doors with locking latches or keyed locks are necessary; Northern spiny-tailed geckos are remarkable escape artists and will exploit even small gaps.

Lighting and Heating

Northern spiny-tailed geckos originate from hot, sunlit regions where natural sunlight provides essential UVB exposure. In captivity, they require access to full-spectrum lighting, including ultraviolet B (UVB). A linear T5 high-output UVB bulb with a 5% to 7% output level works best in this scenario and should be mounted approximately 12 inches from the gecko’s primary basking location. The UVB tube should span at least half the length of the enclosure and be replaced every 12 months, even if it still appears functional, as UVB output degrades over time.

A proper thermal gradient is crucial for this species’ thermoregulation. The basking area should maintain a surface temperature of 85–95°F. The warm side’s ambient temperature should range from 80 to 85°F, while the cool side should remain near 75–80°F. At night, a safe drop in temperature is acceptable and natural, with ambient enclosure temperatures falling between 65 and 72°F. All heating elements — including ceramic heat emitters, radiant heat panels, or deep heat projectors — must be connected to a reliable thermostat to maintain consistent and safe temperatures. Heat rocks must never be used due to the high risk of thermal burns.

Photoperiods should replicate natural seasonal changes. A 12-hour light and dark cycle is suitable for most of the year, with variations of up to 14 hours of daylight during summer months and down to 10 hours in winter to encourage natural circadian rhythms and seasonal hormonal cues. Seasonal adjustments to both photoperiod and temperature can support breeding cycles and overall health.

Substrate and Enrichment

The Northern spiny-tailed gecko requires a substrate that mirrors the sandy, semi-arid soils of its natural range. A blend made with sand and a portion of ReptiEarth for mild moisture retention, provides a realistic and safe substrate that encourages natural behaviors such as digging and thermoregulating through selective substrate contact. This mixture holds tunnel structure well, minimizes impaction risks, and maintains proper hydration without encouraging bacterial growth.

These geckos are highly responsive to environmental enrichment and benefit from a dynamic, multi-level environment. Strategically place branches and rocks to provide climbing opportunities and facilitate behavioral thermoregulation. Allow for the construction of hiding zones both above ground and within substrate banks. Flat basking stones placed under the heat source will provide ideal thermal spots for digestion. Incorporating dry leaf litter and occasional rearranging of enclosure items can encourage exploratory behavior and alleviate boredom.

At least two secure hiding locations must be included: one in the warmer zone and one near the cooler side. Additional crevices or cork hides higher in the enclosure provide observational points and reduce territorial stress. These geckos are typically solitary in captivity and should only be housed together when breeding, and even then, only under closely supervised conditions with sufficient space and visual barriers.

Humidity and Hydration

Though native to semi-arid regions, the Northern spiny-tailed gecko still requires controlled humidity levels to maintain healthy skin, mouth tissue, and respiratory function. The ideal relative humidity should average between 30% and 50%, with localized spikes during shedding cycles. Daily light misting of one side of the enclosure — preferably the cool side — is advised to preserve humidity microclimates, particularly inside a humid hide. Never mist the entire enclosure heavily, as overly wet conditions can encourage bacterial or fungal growth.

To achieve proper hydration, a shallow but sturdy water dish should always be available and cleaned regularly to prevent biofilm buildup. Ensure it is accessible but not easily tipped. In drier household climates, the addition of a small cool-zone humid hide filled with moist sphagnum moss or damp ReptiEarth can help prevent shedding complications and chronic dehydration.

These geckos primarily absorb ambient moisture through drinking droplets, so fine misting during early morning or just after lights out can simulate dew behavior and encourage drinking. This species has been observed licking condensed water from enclosure surfaces or climbing structure. To monitor the enclosure’s humidity accurately, use a calibrated digital hygrometer with probe sensors rather than analog dials, which are often inaccurate. Proper monitoring ensures the gecko’s environment remains within the optimal range and adjustments can be made with seasonal fluctuations in room humidity.

Diet & Supplementation

The northern spiny-tailed gecko is insectivorous, with a diet that consists primarily of arthropods in its natural habitat. In the wild, it forages mostly at night, preying on a variety of invertebrates such as beetles, crickets, moths, spiders, and occasionally smaller orthopterans. This species relies heavily on active foraging to locate prey, often moving across rocky outcrops and dry woodland floors under the cover of darkness. It uses visual cues to detect movement and locate prey, supported by highly sensitive eyes that are adapted for low-light conditions. Chemical cues may also play a role, especially when detecting prey hidden under rocks or within leaf litter.

Feeding strategies in the wild primarily involve stalk-and-strike behavior. The gecko exhibits stealth movements toward prey before lunging swiftly to grasp it in its jaws. Unlike constrictors or venomous reptiles, this gecko has no specialized prey immobilization strategies; instead, it relies on speed and accuracy. Once captured, prey is typically subdued and swallowed whole. This hunting method requires prey that is appropriately sized and of manageable physical resistance, which often leads the gecko to target soft-bodied invertebrates or those with minimal defensive adaptations.

Dietary needs and feeding behavior change according to the animal’s age and the season. Juveniles feed more frequently than adults and generally consume smaller, softer prey items. As they mature, they are capable of handling larger, more robust arthropods. Seasonal variation in prey availability can influence diet breadth. During warmer months, when insect activity is at its peak, the gecko feeds more frequently to meet increased metabolic demands. During cooler periods or dry seasons, feeding activity may decrease, and the animal may become semi-torpid, leading to longer fasting intervals. This seasonal variation should be mirrored to some degree in captivity to promote natural metabolic rhythms.

In captivity, replicating the wild diet as closely as possible is essential for maintaining proper health. The mainstay of a captive diet should include a rotation of live insects such as crickets, dubia roaches, black soldier fly larvae, and appropriately sized mealworms. Wild-caught insects should be avoided due to the risk of pesticide contamination and parasites. Because captive insects often lack the nutritional variety found in wild prey, supplementation becomes critical. All feeder insects should be gut-loaded for 24–48 hours with a high-calcium, nutrient-rich diet prior to being offered. Additionally, calcium powder with D3 should be dusted onto prey items at least twice a week for juveniles and weekly for adults. Depending on the UVB lighting used in the enclosure, vitamin D3 supplementation may need to be adjusted accordingly to prevent metabolic bone disease.

Captive feeding challenges may include refusal of food due to stress, inappropriate environmental conditions, or monotony in prey items. Offering a variety of insects with different movement patterns and sizes can stimulate natural foraging responses. Feeding should generally occur in the evening or at night to reflect the gecko’s nocturnal habits. A proper feeding schedule entails offering food every other day for adults and up to five times a week for juveniles, taking care to adjust intake to prevent obesity—an increasingly common problem in captivity due to overfeeding and lack of activity. Signs of malnutrition such as weight loss, lethargy, or soft jawbones necessitate immediate dietary evaluation.

To encourage natural feeding behaviors and reduce stress, environmental enrichment methods should be incorporated into the enclosure. This includes placing feeder insects in crevices or among foliage, simulating the need to hunt rather than just feeding from a dish. Use of live prey that moves unpredictably can also help maintain the animal’s physical condition and cognitive engagement. By closely mimicking the physiological and behavioral cues experienced in the wild, keepers can provide a nutritionally balanced, stimulating environment that supports the long-term health and well-being of the northern spiny-tailed gecko.

Reproduction

The Northern spiny-tailed gecko is a small, arboreal gecko that exhibits notable sexual dimorphism, with adult females generally being slightly larger and possessing a more robust body shape, while males exhibit broader heads and precloacal pores which are used to excrete pheromones for attracting mates. Reproductive maturity is typically reached by 18 to 24 months of age when individuals have reached sufficient size — usually around 4 to 5 inches in total length. Mating behavior is seasonal and strongly driven by environmental changes that mimic the gecko's natural arid and semi-arid habitat in northern Australia.

During the breeding season, males become more active and display territorial behavior, frequently licking or nudging females as part of courtship. Courtship may involve body vibrations and tail wagging, which are believed to signal reproductive readiness. Males will often follow receptive females and attempt copulation by aligning themselves alongside the female’s body and wrapping their tail underneath to facilitate cloacal alignment. If the female is unreceptive, she may vocalize, lash her tail, or flee the encounter. Mate selection often appears to be driven by both the hormonal cycle of the female and her response to male courtship displays. In captivity, precise observation of behavior is necessary to identify compatibility, as not all pairings result in successful copulation.

Environmental cues play a central role in initiating reproductive readiness. In the wild, this species breeds during the warm, wet season, so simulating this in captivity is essential. A seasonal drop in nighttime temperatures to around 65-70°F for six to eight weeks in the fall and winter can mimic the natural cooling period of their habitat. This “brumation” period, during which feeding is reduced and activity levels decline, is often necessary to prepare both sexes for successful breeding. In late winter or early spring, returning to daytime highs of 85–90°F and raising nighttime temperatures to 70–75°F, along with increasing daytime light exposure to 12–14 hours and raising relative humidity levels to 50–70% via misting, helps to mimic the onset of the rainy season and stimulate reproductive behavior.

This species is oviparous, laying soft-shelled eggs in hidden, humid microhabitats. Copulation must be followed by access to a suitable egg-laying site for the reproduction cycle to complete. In captivity, females require a moist nesting substrate such as damp ReptiEarth or sphagnum moss within a sheltered laying box. Without an appropriate site, females may retain eggs, leading to potentially fatal complications such as dystocia. Additionally, providing multiple hide areas for both sexes is essential to reduce stress and establish territorial boundaries, as some individuals may become aggressive if confined with unsuitable partners. Though the species is not highly gregarious, short-term cohabitation for breeding is possible with closely observed, compatible pairs.

Common challenges in captive breeding of the Northern spiny-tailed gecko include incompatibility between potential mates, environmental stress, and over-conditioning due to inconsistent seasonal cycling. Males may become overly assertive if housed with females continuously, leading to stress or injury. To mitigate this, animals should only be introduced after a cooling period and upon signs of reproductive emergence. Enclosures should be set up to allow swift separation if aggression occurs. Stress from improper temperatures, lighting, enclosure size, or humidity can suppress reproductive hormones. Providing a seasonal environmental routine that closely follows natural cycles significantly increases the likelihood of successful breeding. Regular veterinary checkups and the monitoring of calcium and vitamin D3 levels are also critical, as gravid females are prone to metabolic disorders when improperly supplemented. With careful environmental control and behavioral observation, however, this species can be successfully bred in captivity by experienced keepers.

Incubation & Neonate Care

The Northern spiny-tailed gecko is an oviparous (egg-laying) reptile, with reproduction occurring primarily during the warmer months, typically from late spring through early autumn depending on regional climate. Females generally lay one or two eggs per clutch, with multiple clutches possible each season under optimal conditions. These geckos require specific incubation parameters to ensure healthy embryo development, and captive breeding efforts must closely mimic natural environmental conditions to maximize hatching success.

The eggs should be incubated in a moist but not saturated substrate such as a 1:1 mix of vermiculite and water by weight. This allows the substrate to retain humidity while preventing the eggs from suffocating or developing mold. The ideal incubation temperature ranges from 78 to 84 degrees Fahrenheit. This range promotes healthy embryonic development and appropriate hatchling size. A slight fluctuation within this range is natural and is generally well-tolerated.

Relative humidity during incubation should be maintained between 70% and 80%. Humidity levels that are too low can desiccate the eggs, while excessive moisture can cause bacterial growth or mold. Incubation typically lasts between 60 and 90 days, depending on incubation temperature. Higher temperatures generally lead to a shorter incubation period but should not exceed 88 degrees Fahrenheit, as this may increase the likelihood of deformities or non-viable embryos. Eggs should be checked periodically for signs of mold, collapse, or other abnormalities, but handling should be minimized to avoid disrupting the delicate internal environment of the egg.

Hatching usually occurs over the course of several hours, with hatchlings emerging through a slit they create using their egg tooth. The young gecko may rest partially inside the shell for some time before fully exiting. Freshly hatched geckos will show a noticeable belly sac, which they absorb over the first 24 to 48 hours. Parental care is absent in this species, and as with most geckos, hatchlings are entirely independent upon emergence.

Neonates are best housed separately from adults to prevent injury or competition for food. A small enclosure—such as a 10-gallon setup with a secure screen lid—is adequate for initial housing. The environment should provide a warm side temperature of 85°F to 88°F and a cool side around 75°F during the day, with a nighttime drop to no lower than 70°F. Humidity should be maintained between 50% and 70%, achieved through daily misting and the inclusion of a moisture-retentive hide box filled with damp sphagnum moss or similar material. Excessive dryness or poor hydration can result in incomplete shedding or dehydration-related complications.

Neonates begin foraging within 2 to 5 days after hatching, once their yolk sacs are fully absorbed. Their first meals should consist of appropriately sized live prey items, such as pinhead crickets or small flightless fruit flies dusted with calcium and vitamin D3 supplements. Feeding should occur every day or every other day, and uneaten feeders should be removed to prevent stress. Clean, shallow water dishes should be provided, although neonates may also drink from water droplets formed during misting. Health concerns in hatchlings include retained shed, dehydration, and metabolic bone disease if calcium supplementation or UVB exposure is insufficient. UVB lighting, while not absolutely essential, is recommended to enhance calcium metabolism, particularly if natural sunlight exposure is not practical.

Handling of neonates should be limited during the early stages to reduce stress and avoid injury, as their small size and delicate physiology make them vulnerable. Over time, brief and gentle handling sessions can be introduced to help them acclimate, using slow movements and secure hand placement to prevent escape or tail detachment. With careful attention to their developmental needs, Northern spiny-tailed gecko hatchlings can grow steadily and transition smoothly into adulthood in captivity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, successful long-term care of the Northern spiny-tailed gecko in captivity requires a comprehensive understanding of its ecological origins, behavioral adaptations, and physiological needs. This species is uniquely adapted to the demanding conditions of northern Australia’s monsoonal and semi-arid landscapes, with specialized behaviors such as ambush predation, territoriality, and seasonal dormancy playing vital roles in its survival. Captive husbandry must therefore closely replicate its natural environment, emphasizing appropriate enclosure design, substrate, thermal gradients, UVB exposure, and microhabitat variability to ensure proper thermoregulation, hydration, and shelter.

Feeding regimens should reflect the gecko’s insectivorous diet, providing a variety of gut-loaded live prey to meet nutritional demands while promoting natural hunting behaviors. Seasonal adjustments in temperature, humidity, and lighting are especially important to support physiological cycles like shedding, brumation, and reproduction. Breeding is best attempted by experienced keepers who can simulate environmental cues critical for courtship, oviposition, and successful incubation, while neonatal care requires specialized attention to developmental needs and growth conditions.

Environmental enrichment, stress mitigation, and close observation of health markers such as body condition, shedding quality, and feeding responses are essential for maintaining both physical health and mental well-being. Regular veterinary oversight, accurate supplementation, and a commitment to ethical sourcing further underscore responsible guardianship of this species.

As a resilient yet environmentally sensitive reptile, the Northern spiny-tailed gecko serves both as a rewarding captive species and a representative of complex arid-zone herpetofauna. With informed care and commitment to best practices, keepers can not only ensure the welfare of individuals in captivity but also contribute meaningfully to the broader understanding and preservation of Australia’s unique reptilian biodiversity.